The Relationship Between FTP and VO2 Max: Understanding it Can Make You Faster

There are many ways to quantify performance in cycling, but two of the most commonly-cited data points are VO2 max and FTP. These metrics are related but distinct, and the connection between them is easy to misunderstand. So what’s the link between VO2 max and FTP, and what role do they play in determining your fitness?

The Importance of Aerobic Fitness

VO2 max and FTP both reflect aspects of aerobic fitness, so it’s helpful to begin by considering what this means and how it affects your cycling.

The aerobic energy system generates energy (in the form of ATP) from fat and glycogen, in the presence of oxygen. This process is called aerobic metabolism and is highly sustainable, capable of powering your muscles at low intensity almost indefinitely with ample fuel.

The downside of the aerobic system is that it can’t power very high-intensity efforts. For short bursts of high power, the anaerobic and neuromuscular/phosphocreatine energy systems take over to quickly generate energy without using oxygen, but these energy systems are rapidly depleted. With a fitter and more capable aerobic system, you can power more efforts with sustainable aerobic metabolism, and save your limited anaerobic resources for when you really need them. This is where VO2 Max and FTP come in.

What is VO2 Max?

The harder you work, the more oxygen your muscles require to power aerobic metabolism—you breathe harder and your heart rate increases during exercise for just this reason. But no matter how much you breathe in, there’s a limit to how much oxygen your muscles can actually utilize. This amount of oxygen can be measured in a lab and is known as maximal aerobic capacity or VO2 Max— The Maximum Volume of Oxygen (O2) your body can consume (sports scientists prefer the word uptake) during exercise.

As an analogy, imagine workers shoveling coal into a steam engine. In this case, the supply of coal represents the oxygen you breathe in, the workers are your circulatory system, and the engine represents your muscles. At a certain point, no matter how large the available supply of coal and how fast the workers shovel it in, the engine simply won’t be able to fit any more fuel or burn any hotter. Additionally, running the engine at this maximum capacity takes a lot of work, and can only be done for short periods of time.

This is essentially what happens when your body reaches VO2 max. It marks the upper limit of what your aerobic system can achieve, and just like in the steam engine metaphor it’s not very sustainable. Once it is reached, only turning on an additional engine (the anaerobic system) can allow further power increases, but as we’ve already discussed the anaerobic system can only fuel brief and fatiguing efforts.

What is FTP?

While VO2 max determines your overall aerobic capacity, it doesn’t say much for your aerobic system’s real-world ability to power sustainable work. That ability is more directly reflected by your FTP, or Functional Threshold Power, the maximum wattage you can continuously produce on a bike for an hour.

FTP closely correlates with lactate threshold, the physiological tipping point at which your body is just barely able to balance the production and clearing of byproducts within the muscles. Unlike VO2 max, it’s influenced by more than just oxygen uptake. Factors such as muscular endurance and anaerobic capacity also play a part in determining FTP, among many others.

FTP is widely used across cycling and within TrainerRoad as a benchmark for fitness and training intensity. This is because the ability to sustain power has a direct impact on almost all aspects of cycling—simply put, the higher your FTP, the faster and harder you can ride for longer. To return to our steam engine metaphor, if VO2 max is the engine’s absolute maximum capacity, FTP is the highest intensity at which the engine can sustainably run for around an hour, without overheating, choking itself out in smoke, or overwhelming the workers shoveling coal.

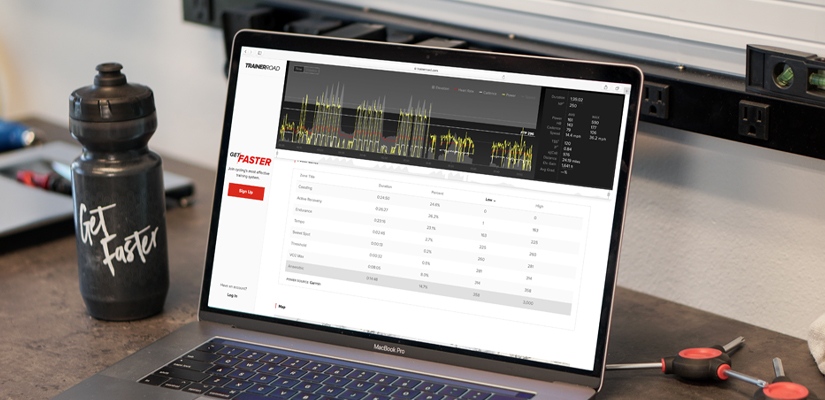

Adaptive Training

Get the right workout, every time with training that adapts to you.

Check Out TrainerRoadDo You Need a High VO2 Max to be a Fast Cyclist?

Here’s where things get interesting. Having a high VO2 max is certainly not a bad thing for an endurance athlete, and many elite cyclists do have awe-inspiring aerobic capacities. But some very successful racers do not—for example, Mark Cavendish’s VO2 max is said to be surprisingly low in comparison to that of many other pros.

All of this is to say that VO2 max is not your athletic destiny, and while FTP and VO2 max are related and can both be improved with training, they aren’t equally important to your cycling ability. Let’s look at a few key reasons why.

Oxygen Uptake ≠ Performance

To start with, let’s consider what VO2 max describes: the maximum volume of oxygen your body can uptake. But cycling isn’t an oxygen consumption contest, and what matters isn’t the volume of oxygen you utilize so much as what you do with it. This is known as pVO2 max, the power you actually produce while consuming a maximal volume of oxygen.

Why is this important? Imagine two athletes have an identical VO2 max, but one is fitter and better-trained. This athlete will be able to produce more power at the same maximal level of oxygen consumption, and will thus be faster. pVo2 max can be improved through structured training, and especially through high-intensity intervals that push you to your maximal aerobic capacity.

Improving Your Fractional Utilization

VO2 max effectively defines the ceiling of what your aerobic system can do, and riding at FTP is sustainable partly because it mostly occurs at a level of oxygen consumption below your VO2 max. Exactly what percentage of your VO2 max you can utilize while sustainably riding is called fractional utilization. The more of your aerobic capacity your FTP can sustainably harness, the faster you’ll be able to ride.

Improving fractional utilization is often both easier and more impactful than improving VO2 max itself. For most athletes, FTP and fractional utilization can be significantly affected by training—both through general aerobic fitness improvements and especially with threshold and sweet spot workouts, which directly target the ability to sustain a high power output. Effective structured training incorporates a mix of these workouts for just this purpose.

The Slow Component

Most athletes associate VO2 max with short, very intense efforts that quickly elevate respiration and heart rate to their limits. But in truth, any work above FTP will eventually push you to maximal oxygen uptake if it lasts long enough. This technical detail is known as the VO2 max slow component and is a result of your body’s decreased efficiency as it works at high intensity. If you’ve ever done a short time trial and noticed that it gets harder and harder to sustain power as your heart rate and breathing gradually increase, that’s likely the slow component in action.

So why does this matter? A high VO2 max won’t necessarily reduce the slow component’s effects. But by raising your FTP and improving your fractional utilization, you can stave off this creeping fatigue with the ability to ride at a greater percentage of VO2 max for longer.

Other Measures of Fitness

FTP and VO2 max are important concepts with significant implications for your cycling ability, but these metrics don’t capture the whole picture. Factors like repeatability, muscular endurance, and your capacity to recover can have meaningful impacts on making you a faster cyclist, and all are dimensions of fitness that steadily improve with training. But these incremental improvements aren’t always immediately reflected in your FTP.

This is why Progression Levels are such a powerful tool. Even if your FTP remains the same, Progression Levels track your ability to complete more difficult workouts across each power zone and directly illustrate the small but meaningful changes that make you faster from day to day. Coupled with structured workouts that systematically target all 3 energy systems, Progression Levels help Adaptive Training personalize your training to make you faster, and allow you to track your progress in greater detail than ever before.

References/ Further Reading

Billat, V. L. (2000). VO2 slow component and performance in endurance sports. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 34(2), 83–85. doi:10.1136/bjsm.34.2.83

Borszcz, F. K., Tramontin, A. F., & Costa, V. P. (2019). Is the Functional Threshold Power Interchangeable With the Maximal Lactate Steady State in Trained Cyclists? International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance, 1–21. doi:10.1123/ijspp.2018-0572

Couzens, Alan. “How ‘Trainable’ Is VO2 Max Really? – A Case Study.” Simplifaster, https://simplifaster.com/articles/how-trainable-is-vo2-max/.

Garnacho-Castaño, M. V., Albesa-Albiol, L., Serra-Payá, N., Gomis Bataller, M., Felíu-Ruano, R., Guirao Cano, L., … Maté-Muñoz, J. L. (2019). The Slow Component of Oxygen Uptake and Efficiency in Resistance Exercises: A Comparison With Endurance Exercises. Frontiers in Physiology, 10. doi:10.3389/fphys.2019.00357