Cycling Cadence: What Is It, What’s Most Efficient, and Cadence Drills To Make You Faster

Cadence is a murky subject for cyclists. We all know that pedaling at one cadence feels very different from spinning at another, and we naturally gravitate towards certain cadences in cycling. But few of us really understand how cadence affects our efficiency on the bike, and there’s lots of contradictory information on the topic. So what actually is a good cadence for cycling, and how can you use pedaling drills to become more efficient?

For more on cycling cadence and training advice, check out the Ask a Cycling Coach Podcast Episode 285.

Table of Contents

What is Cadence in Cycling?

Cycling cadence is the speed at which you turn the pedals. It’s expressed in rpm (revolutions per minute) and can be measured with inexpensive sensors. If you have a power meter on your bike, it probably measures your cadence automatically. On fixed-gear bikes, cadence increases proportionally with speed, so the faster you go the faster you pedal. But geared bikes allow you to maintain a relatively constant cadence by shifting as your speed and resistance change.

What is a Good Cadence for Cycling?

Cycling cadence varies widely from rider to rider, and in different situations. Generally, a good cadence in cycling is between 80-100 rpm. Beginner cyclists often pedal rather slowly, around 60-85 rpm. Racers and more experienced hobbyists usually average between 75-95 rpm, and pros can sustain over 100 rpm during attacks or more than 110 rpm during sprints.

Adaptive Training

Get the right workout, every time with training that adapts to you.

Check Out TrainerRoadDifferent cadences make different physiological demands on the body. Low cadences require more force to be exerted in each pedal stroke, placing a greater burden on the muscular system and activating more fast-twitch muscle fibers. High cadences typically involve less force per pedal stroke, shifting the load to the cardiovascular system and slow-twitch muscles. But as we’ll see, the effect of different cadences is even more complicated than it might seem.

What is the Most Efficient Cadence?

Here’s where things get interesting. There’s lots of good evidence to support the idea that lower cadences in cycling are more bioenergetically efficient. When you pedal faster, oxygen consumption increases, even if the same amount of work is being performed. From this simple standpoint of metabolic efficiency, research shows the optimal cadence is around 60 rpm—a speed most cyclists would charitably characterize as a grind. This pace isn’t sustainable for most of us, for an important reason—there’s more to riding a bike than being efficient.

The other half of the equation is power, and the ability to generate it. At low cadences, your muscles contract at speeds well below the rate at which they are strongest. As the power you’re trying to create rises, the cadence at which your muscles are most effectively able to produce it increases, too. So while pedaling slowly has the lowest overall metabolic cost, it effectively limits your ability to produce high power, a dealbreaker in most race scenarios.

In the end, the science is confusing and sometimes contradictory. But a wealth of evidence suggests the most effective cadence depends on situation and event type. Low to moderate cadences of 70-90rpm are comparatively weak but efficient, and useful for ultra-endurance riding when energy conservation is of primary concern. High cadences of 90-100 rpm are better for most racing and time trial situations, in which power production is most important. And very high cadences of 100-120 are most effective when the highest power is needed for short periods, such as during attacks, surges, and sprints.

Should I Train at Different Cadences?

Yes! Cyclists of all disciplines inevitably encounter situations requiring cadence changes, such as steep climbs or hard accelerations out of corners. These crucial moments can be very fatiguing if you’re unprepared to face them. Practice and experience make perfect, and acclimating yourself to a wide range of cadences in training can help you be ready on race day.

Cadence drills also improve the quality and efficiency of your pedal stroke overall. In fact, studies of professional cyclists have shown that some elite riders are actually most efficient at high cadence, despite the previously-discussed evidence that low cadence is most economical. This is likely due to pro athletes’ fluid movement patterns and good form, learned through practice. For all these reasons, simple cadence drills can benefit every rider.

How to Improve Your Cadence

Cadence Drills can be incorporated into almost any easy or moderate workout to rehearse movement patterns and develop efficiency. The Base Period is an excellent time for this, since establishing fluidity early in the season is easier than correcting entrenched habits later on.

While cadence drills are typically thought of as a base season focus, you can sprinkle these in at any time during your season. Cadence drills are never about producing higher power overall—the goal is developing good form. Incorporate them into low-stakes riding or steady-state work where they don’t compromise your ability to meet a power target. You’ll likely feel awkward at first, but improvements can come quite quickly. Here are some of our favorites.

- Endurance Spinning

This drill is great practice for raising your natural, self-selected cadence. As you are riding, increase your cadence 3-5rpm and hold for five minutes. If you heart rate increase by more than a few beats per minute, reduce your cadence. Once you finish the drill, pedal normaly for a few minutes before repeating. - Single-Leg Focus

The goal of single-leg focus drills are to develop your ability to apple power more effectively through the entire pedalstroke and is best complete on the trainer. For 90 seconds, devote all your attention to one leg and pay attention to lightly pulling your foot across the bottom, lighly lifting your knee upward, then softly kicking over the top. Pedal for a minute, then switch your focus to the other leg. - Isolated Leg Training

Similiar to single-leg drills, isolated leg drils see to develop the ability to apply power through the entire pedalstroke. While on the trainer during a low-power interval, completely unclip one foot and rest it on the trainer, stool, or anything eslse that allows you to safely keep is out of the way. Start with a slow cadence and pedal with one leg for 10-20 seconds. Pay close attention to the bottom and top of the pedalstroke. Any deadspots in your pedaling will result in a “knocking” sound. Keep tension on the chain and switch legs anytime your form degrades; don’t practice bad habits just to tack on 5 or 10 more seconds. - Kick and Pull

These reinforce your ability to maintain tension through the weakest portions of the pedalstroke, the top and bottom quadrants. As your knee approaches top-dead-center, lightly kick your toes into the fronts of your shoes, and as your feet approach bottom-dead-center, lightly pull your heels into the backs of your shoes – kick and pull. Focus on just the kick for 30-60s, just the pull for 30-60s, then eventually both for 30-60s simultaneously.

Cadence Drills in TrainerRoad Workouts

Many TrainerRoad workouts incorporate optional cadence intervals, especially during the base period.

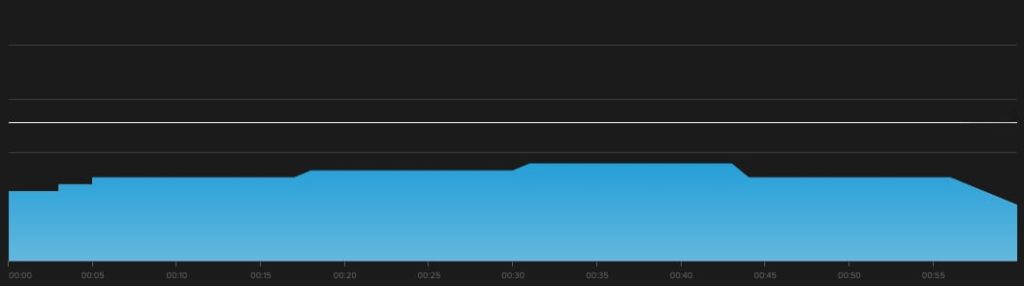

Pettit is one example. This aerobic endurance workout and includes form sprints, speed-endurance intervals, as well as pedaling-quadrant drills. Since this workout is so easy, it’s a great chance to practice skills and pedaling mechanics without compromising interval quality.

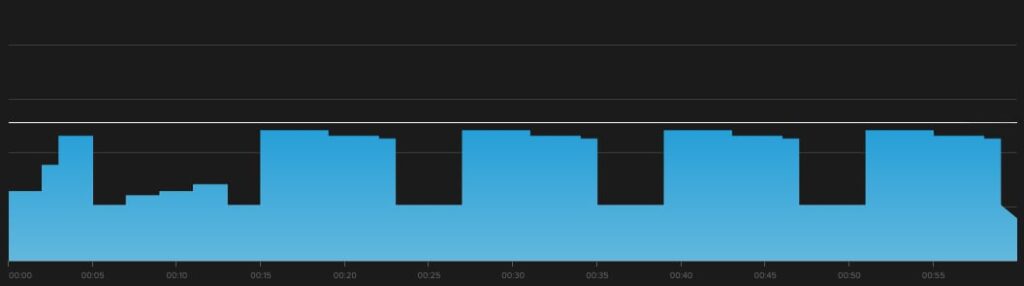

Another example is Ericsson. In this sweet spot workout, cadence drills are incorporated into the intervals themselves. Riders begin with a slightly quicker-than-usual spin for the first 4 minutes, increase their pedal speed for the following 3 minutes, and then spin all-out for the final minute. These drills aim to improve sustainable leg speed and fine-tune pedaling economy.

Cycling Cadence for Triathletes

One final aspect of cadence to consider is how it might impact the subsequent run during a triathlon. Since multisport events reward athletes who can conserve energy across a race, an economical cadence would seem to be beneficial. Indeed, some research confirms this idea. Several studies have shown that running time-to-fatigue is reduced after a low-cadence bike leg, and that low cycling cadence increases efficiency on the bike and afterward in the run. For triathletes, a slightly slower pedal stroke probably is better, overall.

But as with all things cadence, there’s a catch. Two studies show that triathletes who ride with a higher cadence at the end of their bike leg start their run at a faster initial pace. In a close competition between evenly-matched athletes, this just might be enough to get a gap and make the difference. It’s also good evidence that even triathletes can benefit from the ability to pedal at a wide range of speeds.

Further Reading/ References:

- Abbiss, Chris & Peiffer, Jeremiah & Laursen, Paul. (2009). Optimal cadence selection during cycling. ECU Publications. 10.

- Bernard, Thierry & Vercruyssen, Fabrice & Grego, Fabien & Hausswirth, Christophe & Lepers, Romuald & Vallier, Jean-Marc & Brisswalter, Jeanick. (2003). Effect of cycling cadence on subsequent 3 km running performance in well trained triathletes. British journal of sports medicine. 37. 154-8; discussion 159.

- Billat, Veronique & Hamard, Laurence & Koralsztein, Jean Pierre. (1999). The Role of Cadence on the VO2 Slow Component in Cycling and Running in Triathletes. International journal of sports medicine. 20. 429-37. 10.1055/s-1999-8825.

- Brennan, Scott & Cresswell, Andrew & Farris, Dominic & Lichtwark, Glen. (2018). The Effect of Cadence on the Mechanics and Energetics of Constant Power Cycling. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise. 51. 1. 10.1249/MSS.0000000000001863.

- Gottschall, Jinger & Palmer, BM. (2002). The acute effects of prior cycling cadence on running performance and kinematics. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise. 34. 1518-1522. 10.1249/01.MSS.000002771.03976.B6.

- Macintosh, Brian & Neptune, Rick & Horton, John. (2000). Cadence, power, and muscle activation in cycle ergometry. Medicine and science in sports and exercise. 32. 1281-7. 10.1097/00005768-200007000-00015.

- Les Ansley & Patrick Cangley (2009) Determinants of “optimal” cadence during cycling, European Journal of Sport Science, 9:2, 61-85, DOI: 10.1080/17461390802684325

- Lucia, Alejandro & San Juan Ferrer, Alejandro & Montilla, Manuel & Santalla, Alfredo & Earnest, Conrad & Pérez, Margarita. (2004). In Professional Road Cyclists, Low Pedaling Cadences Are Less Efficient. Medicine and science in sports and exercise. 36. 1048-54. 10.1249/01.MSS.0000128249.10305.8A.

- Tew, Garry. (2005). The Effect of Cycling Cadence on Subsequent 10km Running Performance in Well-Trained Triathletes. Journal of sports science & medicine. 4. 342-53.

- Vercruyssen, Fabrice & Brisswalter, Jeanick & Hausswirth, Christophe & Bernard, Thierry & Bernard, Olivier & Vallier, Jean-Marc. (2002). Influence of cycling cadence on subsequent running performance in triathletes. Medicine and science in sports and exercise. 34. 530-6. 10.1097/00005768-200203000-00022.

- Vercruyssen, Fabrice & Suriano, Rob & Bishop, David John & Hausswirth, Christophe & Brisswalter, Jeanick. (2005). Cadence selection affects metabolic responses during cycling and subsequent running time to fatigue. British journal of sports medicine. 39. 267-72. 10.1136/bjsm.2004.011668.