This is what products like WHOOP are trying to solve for.

And Training Today (Apple Watch app), and Garmin Body Battery, and…

WHOOP is the only one (to my knowledge) that refers to it as “strain” specifically, but there are lots of players trying to figure it out…

If you can’t measure it, or try and it doesn’t appear help, then IMHO its time to invest more time learning to listen to your body. Or spend a lot of money on ‘lab testing’ that may or may not provide performance gains.

Not true…

Did my first DIY lactate test yesterday (see other topic). LT1 between 217-229. Next day I will do another test I think but with longer steps and a smaller range (200-230W) to confirm my value. Goal is to create a range for my ISM Z2. And then build TIZ for this range.

So let’s say LT1 = 220W, that’s 81%FTP and HR is 136 ( 82%LTHR / 75%maxHR )

For the purpose of the conversation, why is lactate problematic? Doing it improperly? Not understanding the numbers? But using an estimate based on a wide confidence interval isnt? Since you said wko is only using 2 points to estimate Cp (The 30s effort is not really suitable for Cp estimate) then it is fitting the rest of the curve with an algorithm.

From a practical sense, wko is less expensive than a lactate meter or getting a full met cart sure, but it is still just trying to fit your data to a model instead of measuring what is actuality happening.

a lot of artifacts & also interpretation errors if you don’t know the whole picture of metabolism, fueling, recovery and so on.

Kind of a general response that could be said for just about any model guiding our training. Why would it be more problematic than a power duration curve?

Testing frequency?

The power number will fluctuate from day-to-day (same as FTP or any other power that you got from an assessment/test). Yes, HR will too. So I would create a range where you triangulate those. So 136 +/- 5bpm (for example), and 220W +/- 10W (with the caveat that short durations outside of those power ranges are fine because we’re not robots). Make note of breath rate as well. Literally count the breath rate over (for example) a 15 sec period.

Why do all that? Because after a certain amount of time (like learning a musical instrument, learning a language, etc) you simply won’t have to go through that mental checklist in realtime. You do it enough that you just know it.

Also keeps you honest when something starts to drift. Remember the end goal isn’t that these numbers or intensities are magic. They are not. They are a way for you to mitigate or anticipate doing too much. Everybody knows they did too much after the fact.

Can you do that all by feel? Maybe, but if you are a good endurance athlete you know how to lie to yourself.

“Cardiac drift can be defined as the upward drift of heart rate over time, coupled with a progressive decline in stroke volume and the continued maintenance of cardiac output. Cardiac drift occurs while exercise intensity remains constant.”

Heart rate increases with power constant over time due to inefficiency. Obv you can train to minimize this, which I guess is the point of the training in this thread, but you cannot eliminate it.

The thing is that the esteemed ISM has added fuel to the fire by recommending pedal to the metal to LT1……so it kind of necessitates proper testing, but I still suggest the old (and fast) method.

Ride a lot, long rides with variable terrain. Once you incorporate the constrains of time and recovery, recurrent 5h rides will tech you how to modulate. This is harder to learn in the trainer but Zwift can help.

Another thing Steve suggests (and has done so in an open forum) is reducing your cycling cadence to 60-75 RPM for these intervals. For me, he also said for every 5 mins I should do 4mins seated/ 1min standing for the duration of the interval.

Now, I don’t know the exact reason for this prescription, but given the hindsight of years and some experience, I can guess …

I believe it is relatively accepted (per a TR blog post, for instance) the a lower cadence at a given power output equates to a lower HR and thus a lower metabolic cost.

I think the aim of this work is to maximize the volume of work (measured in KJs) at the absolute lowest possible cost … which can only be monitored by HR for most of us.

I’ve noticed the lower cadence and sit/stand prescription has 2 other benefits … maybe 3: 1) eases the pressure on your undercarriage during long trainer rides due to increased torque, 2) makes the workout more engaging due to the constant variance — i.e. it breaks up monotonous intervals, and 3) (possibly) injury prevention, by constantly changing your biomechanics and engaging other muscles groups to keep you more likely to stay aligned, etc.

I would also caution that if you have knee pain at lower cadence … STOP. Get that fixed first. I think you‘ll only make things worse if you pedal through knee pain of any type.

I now do all my SweetSpot/tempo work on the trainer work at-or-below 75 RPM, and do all my Threshold/Vo2 work above 95-100 RPM now out of habit. Outside, my natural cadence is in the 90-92RPM range.

Just some more food for thought.

EDIT: Here is the TR blog post that discusses cycling cadence and the lower metabolic cost of Lowe cadence:

When I was using Steve I got the impression it was to help lowering your Vlamax. (If indeed Vlamax is a thing)

There’s been a lot of debate in the coaching community lately on torque training. Lots of threads on twitter. KM and Coggan basically based torque training recently on a podcast.

I quote this because this thread led me to reading the Norwegian Method again. There are lots of similarities to Steve’s tempo training IMO. Here’s the link:

https://www.mariusbakken.com/the-norwegian-model.html

He sums it up:

I do believe a major factor of this “sweet spot” is due to muscular factors, which in my opinion is the main limitation to training stress, also the main reason for overtraining. You get the huge benefits of pushing the threshold high at the least possible wear of the muscles; therefore you can do loads of this type of work.

He says “threshold” but if you read the page, it’s at a lower lactate level which is probably tempo.

Neal also talks about “blocking” workouts. For Neal, it’s two tempo workouts on consecutive days. Bakken is talking about multiple sessions per day.

- Blocking up the threshold work into a given short time frame, with several threshold sessions daily followed by at least one easy training day.

If anyone is interest in the Norwegian Method, I recommend Steve Magness’ podcast:

I’ve also been fascinated by the “floating” intervals Bakken mentions. Magness calls them “flux” training and you’d find several podcasts on those. They are basically “over unders” or “under ats”.

After my rides I review torque/force, some of my low cadence endurance rides have the same torque/force as sweet spot rides at 90rpm.

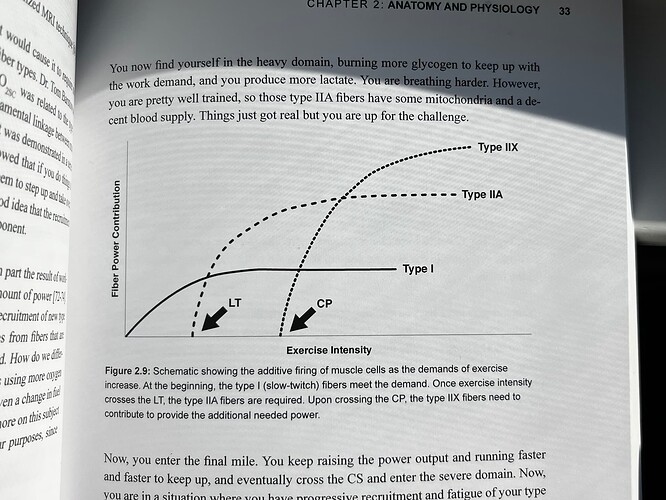

Right or wrong I believe that low cadence can drive additional muscle recruitment, from Dr Phil Skiba’s Scientific Training for Endurance Athletes:

and

One recent read on anecdotal evidence for low cadence is in this article:

For some reason I improve performance by doing low cadence work. I don’t know if it is mental ‘believe it and it works’ or getting used to pushing harder for longer or some physiological reason. I didn’t believe it at first, ‘discovered’ it my first and second season after doing century club rides with long climbs, at low cadence and low intensity because compact gearing only goes so far at 2.5-3.0 W/kg. It is repeatable, season after season after season. I can’t explain it other than to point at performance increases.

Really doesn’t matter, it works for me and repeatable results are superior to someone on a podcast or forum explaining why it shouldn’t work.

FWIW I can go from low cadence endurance work with a 10-min SS interval or two, to doing 1x60 to 1x90 at 85-90%. Thats one heck of a progression.

Thanks for the podcast link. Also thanks for mentioning Fast Labs forum - I had no idea they had a free membership option

Very interesting take from Skiba. I wonder if that threshold/fiber type figure is how most people think about it? Not passing judgement on something published like 15 years ago but it’s incorrect based on the current body of lit, and even using older available data sets from 80s papers could easily be proved wrong.

I appreciate the motor unit recruitment theory though. In WD#9 we discussed exactly that as being a benefit of actual strength training and easily could be the mechanism here (to be clear: motor pattern specific neural drive). I bet there’s some contractile energetics that benefit but my best guess is this is what’s happening with “torque training”. In WT folks who do it and put out new lifetime bests I also wonder what this kind of training replaced, and what most of them aren’t doing. In the data sets I have for those doing it, I don’t see any anaerobic capacity training, threshold type stuff, etc. It seems mostly to be tempo, torque stuff, and a couple harder efforts around racing.

Wasn’t Skiba’s book published just last year? Or did I misunderstand your comment?

First off, I want to be clear it is not Skiba’s take on torque training. I don’t recall seeing anything on torque training but I need to reread the book.

From your earlier WD podcast I learned about Henneman’s size principle. That picture, to me, is illustrating the concept of the size principle. Emphasis on the word concept. But I’m an engineer with no training in physiology or biology. So its a bit of a struggle sometimes keeping up with the bio stuff on the pod.

Listened to WD#42 yesterday and as a person of size (ahem, 90+kg) and a math brain, was fascinated by the intro to allometry. And the rest of the pod too, it has been awhile so I just tossed a Jackson into the tip jar. Cheers.