To be clear, the data showed linear improvements with increasing arbitrary units determined by the product of volume and intensity, particularly when we remove sprint interval training. But the highest AU in the study wasn’t exactly the highest stimulus that one would find in a higher training program, nor should one expect that anyway. So here’s that data, and there are a lot of potential ways to interpret this data and we didn’t go into all of them in the pod, so it would be pretty fun to look at the other angles.

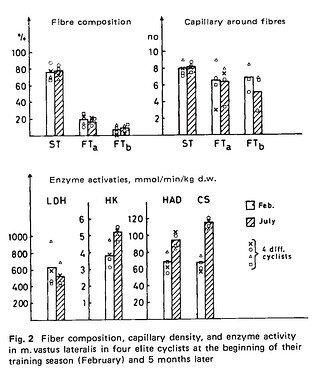

As far as I’m aware, there are no longitudinal cohorts looking at what physiologic changes occur with very high volume training, and the cross sectional data leaves a lot to be desired. I actually expect what we’re looking at in the above data is the bottom of a logarithmic curve, there’s just not enough published data looking at higher training volumes. Here’s an example of some data in professional cyclists through a season:

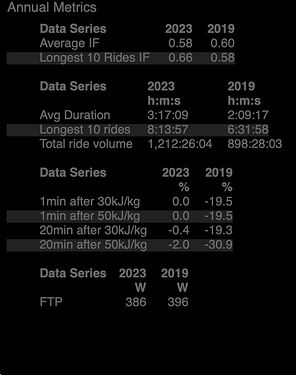

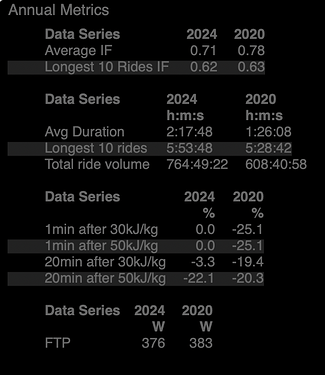

My coaching experience suggests that there isn’t an upper limit (hence my thought that it’s a logarithmic curve), which is Bishop’s interpretation also, except mine includes my coaching experience and afaik his is limited to the data set in this paper. I have a lot of data suggesting that fatigue resistance, durability, endurance, whatever we want to call it, is massively improved by more low intensity riding. Here’s two examples of pro male riders, the full year before starting to work with me, and the most recent full year working with me. The big number to watch is % loss after 50kJ/kg (what I use for pro men, with some exceptions).

This is an all rounder. Not a huge change in average intensity or FTP (it went up to 410-420w; the season was so busy we didn’t do any full FTP testing other than what was done with intervals) but fatigue resistance delta was… well you can see, and it’s made a world of difference. The longest 10 rides usually included intervals as well, but most of the riding was around 50-55% FTP.

This is a sprinter so a different challenge. What I care about is in the 1min range and having that available on race day. Again, busy season and no formal power testing besides what was done with intervals, but FTP went up to about 400w. Pmax up from 1700w to 1900w. Lacking representative efforts on 20min since he usually phones in those last climbs to save legs for sprint stages.

To me, this is where the published data falls short, especially if we want to presume our usual measured physiologic changes data = performance. We don’t have to look far to see a disconnect between an outcome and the expectation based on a measured value, like people not performing well with full glycogen stores, or lab animals with an endurance phenotype but without endurance performance, or type II fibers with high mitochondrial content and fat oxidation enzymes, etc etc. So it’s real world observations like the ones above that we’re forced to draw a lot of conclusions from since it starts and ends with performance. Maybe eventually we’ll figure out everything going on under the hood. We sure don’t have a truly comprehensive understanding yet, which I thought was pretty well known so I haven’t spent much time discussing it anywhere, but lately I’ve been finding it’s probably not as generally understood as I thought.

Addressing the original question, I do find that “z1” does indeed provide meaningful benefits in large enough quantities, even though what little I could find on the effects of touring in trained cyclists (selected for their likelihood to complete the protocol) was not perfect due to some methodological choices, but suggestive of some good benefits to increased gross efficiency and some mitochondrial mass improvement, for riding at an average of 47% GXT max. The substrate oxidation data suggests to me (but doesn’t prove) big improvement of first threshold and possibly an improvement of second threshold. No VO2max improvements of note, since as expected for trained cyclists, the intensity was too low to get improvement there (aka no hard intervals). Substrate use and biochemical response to a 3,211-km bicycle tour in trained cyclists - PubMed

If we’re looking at something like Coggan power levels, there’s probably not much difference between the upper reaches of z1 and lower reaches of z2 since physiology is continuous. And none of these address the question of where we’re riding relative to first threshold. Quantity has a quality all its own, as the saying goes. My observation is that volume is volume, but that alone does not a training program make. So while giant touring weeks like this are awesome and most of my clients/consultees find them to provide great benefits to endurance lasting for several weeks to several months, if you’re fairly well trained already then on their own they’re likely not going to lead to a big improvement in aerobic capacity (as seen in the above linked study), which is what I think most people are hoping for when it comes to volume. And as psmith suggests, we can’t easily factor out confounders like initial fitness, extra climbing and headwinds, and other things that would increase the intensity and particularly have an impact on muscular endurance (also present in that study).

The bottom line for me is that there’s really no delineation of a lower bound where we do or don’t get a benefit. As we get better and better trained, both in a season and year over year, the improvements in anything will be smaller and hence harder to measure, especially in study where you’ll need large n to find a small effect size. So even though it can be difficult to measure outcomes related more to endurance than vo2max, the very practical answer is that if it feels like it was a good stimulus, it was probably a good stimulus.

I hope it was fun, and please post a couple pictures!